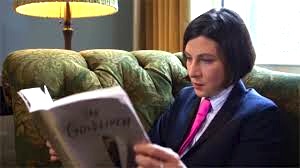

photo by BBC

The Beginning

The hardbound book’s impeccable packaging invites us and signals quality.

The novel’s opening pages with their lengthy lyrical sentences give a powerful impression that we’re in for something special. Something in the heavyweight league. The exquisite use of language and pace makes me think about how remarkable the audio version of this book would sound.

At the onset we get a vivid description of the narrator’s hotel hideout room and a strong sense of his desolation beside one of Amsterdam’s green canals. What is his source of despair? Of course, we also wonder what’s the controversy outside and why he is avoiding it. Meanwhile the narrator, perhaps because of his solitary situation and the excess of lukewarm vodka, is overcome with thoughts of his mother, who is depicted in stunning consecutive sentences that detail her appearance and demeanor. Then we learn how he lost her and the underlying story launches.

The tired writing rule that one or two character particularities goes a long way, and another rule that exposition interferes with dramatic scene …both are about to be blown to bits by Donna Tartt’s talent.

Part I

What we have in the book’s opening act is the initial storyline patiently presented, along with a rich startup array of interesting characters, major and minor — though this early in the book it’s impossible to say which are merely minor. Some reappear after the explosion, like Pippa, who Tartt (during her amazing bomb description) telegraphed that we were likely to see again. Some reappear as dead people memories. Others, including the artfully portrayed Harbour family, and guys like Cable and Hobie…we’ll see how far they go.

It’s interesting to note that any shrinks, educational overseers, or investigators etc. assigned by the state to check on Theo’s welfare are unfavorably described, which is consistent with Theo’s silent disdain towards them. Despite best efforts by the magnanimous (and filthy rich) Mrs. Harbour, her good-humored husband and polite son Andy, Theo is withdrawn and sealed up until he finds Hobie. The return of Welty’s ring to a living connection authenticates Theo’s memory and, adding in the reunion with Pippa (all of this in the “Morphine Lollipop” chapter), his existence takes on a new, more hopeful light.

Tartt, an admitted fan of Dickens, is (so far anyway) doing the Copperfield/Twist/Pip bit: placing a young man in a dire and/or peculiar situation and bringing us along with him as he navigates and grows up. His path is strewn with tragedy and loneliness and a barrage of strangers and renewed acquaintances who assist or hinder his path forward. The big difference is Theo is an American boy in 21st century Manhattan.

Donna Tartt is masterful in these early chapters, unfolding the story in a way in which we are attentive to and empathetic with the new orphan Theo. When we quit reading and turn off the light, the concern for him remains. Others are interesting too, and we want to see them again. That is, the book is beginning to own us.

Parts II & III

The contrast between Park Avenue and Vegas is a shock to Theo and to us too. Tartt conveys the stark differences with humor, sharp details, and shredding imagery. We recognize Vegas’s cheesiness and plastic quality, and the tackiness of his father’s home is signaled right away by the faux elegant name of their cookie-cutter development, presented by the author in faux elegant font: The Shadows in the Canyons.

Theo’s father is a drunk and a bad gambler, and his girlfriend Xandra is a thief and a loser. The contrast in style and behavior to the graciousness of the Harbours is staggering. Our only consolation at this point is that Theo managed to get the painting out of NYC and has it there with him.

It’s really clever that when Theo left, the Park Avenue doormen were his support group. They too mourn the loss of Mrs. Decker and are Theo’s close allies. Theo cleverly speaks Spanish to them. One, the Puerto Rican, says he misses the warm weather and is a “tropical bird.” Which plays on the painting that the doormen hold in a suitcase for pickup by Theo (which he later unwraps in his colorless Vegas room and sees as contrasting bright and rich — tropical).

Boris’s supposed exploits are excessive and his Ukraine talk is over the top, but sometimes fiction asks us to suspend our doubts and go with things. Plot-wise he’s functional …(so far –I cant speak for the pages ahead) … functional as the worldly influence kid, an entertaining ingredient in Theo’s coming of age. Does the movie title “Iceberg SOS” foreshadow anything?

Classic scene: Dad’s compensatory holiday dinner at the extravagant restaurant on the Strip. We see more of America’s greed and misplaced values through the eyes of Theo and the Russian Boris, in particular.

The thought came to mind, how does Tartt manage to capture the lives of teenage boys so well? Maybe she took their three main activities and took off from there: fighting, getting drunk or high, and obsessing on girls. That’s what Theo and Boris are into. Boris, however, brings more criminal mischief, some homo-erotic closeness, and his own domestic traumas that he tries to disguise. He exudes an overall sense of unreliability and danger, not unlike his bipolar dad.

Odds and ends in Tartt’s Parts II & III tapestry:

- Climate change. she brings in vivid yet understated descriptions of the erratic weather out West.

- The economy: the mostly empty and unfinished neighborhood (Canyon Shadows) depicts the fall of housing and death of the boom (Bush Recession) in the expanded exurbia of Las Vegas.

- Modern Girls into Renunciation: Kotyu.

- Drug excess: the boys take everything except heroin and drink vodka straight from the bottle.

- Modern wake: Xandra and her loose pals getting totally messed up

- Nineteenth century novel type journey: Theo’s bus ride back East with a tiny dog in a box w/crusty yet charitable driver

- Replacement of cozy old building of value with a new and overpriced greed palace

Part IV

Past midway, it’s the biggest time jump in the book so far: eight years later. Could be a moment in the narration to be reflective and have the story decelerate, but Tartt doesn’t go there. She keeps rolling out surprises and moves relentlessly ahead with event after event to keep us engaged. It’s true, though: this series of chapters has a lot of packed tight exposition. But it’s interesting exposition.

So far, the section is loaded with loss: people who are dead, gone, or are not themselves anymore. Pippa has a boyfriend, which makes Theo crazy. The old homestead is gone, the Harbours are shattered, and Boris is still en absentia. There are problems brewing at Hobie’s shop and some less than honest dealings have put our protagonist in a difficult spot.

Theo falls heavier into drug use. He is threatened by the sharper Lucius, who has figured things out. The story jumps again, and Theo is engaged to the vapid Kitsey, and they shop for china patterns. We think, here we go again, Theo has stepped into a mess and seems to make it more of one. He is now less favorable a character to us (our sympathetic mood changes, that is) because he has money and free will and keeps getting in his own way, making mistakes that cause us to want to shake him.

Things look foreboding as he runs into Boris, and they proceed to some heavy vodka drinking in the Village…

Part V –

Theo’s dark descent into despair appears to be over. Theo’s world is momentarily stabilized by his engagement to Kitsey, a relationship cultivated by her mother, Mrs. Harbour. Not all is as it appears. Again, Theo is in and out of other people’s hands, blown around by circumstance, his fate coming through no real control of his own. This is best demonstrated in the engagement party where he is a role player but not a person, entangled in a high risk situation. Only in the prior scene, during his movie and dinner with Pippa, do we get to see him truly as the Theo he would want to be…and what he is capable of feeling for another. Yet even making small decisions is something he finds difficult. He is sitting on the fence now, romantically, as if his other problems weren’t compound enough, and his judgment is clouded by long drinking and drug sessions.

Boris eventually brings him into the big league world of art theft and thuggery. He takes him into his world of crime and paybacks, whisks him away from the Kitsey situation, and puts him to use overseas.

Their mission to regain the Goldfinch takes the book out of the milieu of a New York love and adventure story and into a drama of international detective-like shoot-em-ups, replete with criminal desperadoes and a lone witness who spoils everything. But it works out…the very beginning put us smack into intrigue, so we knew the loop would come around again….

Theo is stranded in a hotel without a passport, and his darkness returns…things rush to a conclusion, yet there are a wealth of epiphanies and reflections at the end…

(NOTE: Will post the last report after I let everything settle -wpm)

Rumor columns say the Salinger estate will release additional works, some of which supposedly pick up characters of yore and take them forward in time. True? Who knows for sure other than a few lawyers?

Rumor columns say the Salinger estate will release additional works, some of which supposedly pick up characters of yore and take them forward in time. True? Who knows for sure other than a few lawyers?