At the midpoint of the Thomas Mann novel The Magic Mountain, the story is pivoting. Protagonist Hans Castorp purposefully extends his stay at the health sanatorium-resort. He no longer entertains the idea of leaving. He is addicted to its regularity. Things seem in order, buttoned up, the German way. He doesn’t admit to feeling detained, or see his doctor’s decree to rest longer in any way diabolical. Others see the light and depart, after the winter thaw and with the advent of Spring. Meanwhile, the bodies of those who die are dispatched to the valley via a long bobsled track.

To this reader any mundane changes or developments seem huge after the first 350 pages of daily minutiae, routine, lots of meals, and multiple character discoveries.

Hans’ conversant and entertaining friend, the humanist Settembrini is moving back to the flatlands. He will miss his stewardship. Worse, Hans’ love interest Clavdia Chauchat has also left, if only for an indeterminate period of time. It’s a cliff-hanger and we expect and hope for her to return – they were just getting warmed up. Hans is left with a copy of her chest x-ray, a bizarre token of his carnal desire.

His steadfast cousin Joachim remains, but he seems to be going into a shell of depression. We can only imagine what may be coming next. I sense a totalitarian aroma brewing in the air, with less happy times at the campground, or an atmosphere diametrically opposed to the first half when life at a supposed clinic seemed more like Club Med for TB patients.

The first half can get exhausting. Blame it on Hans, who went to the mountain just to visit. He’s not really sick, but is definitely foolish and openly presumptuous. His explanations of the slightest matter are tedious and overly abundant. He wants to be feverish. He likes it there. A victim of his own making, he falls into traps. He studies anatomy so he can understand flesh. Things happen. Often funny things or embarrassing moments. Long, high-falootin’ academic conversations happen. Trifling and gossipy conversations happen as well. Eerie and kinky things happen with the authoritarian doctor and his lady patients, stuff kept secret in the basement, in contrast to the luxurious meals and behavior games taking place openly in the dining room, three meals a day. The tone of the narrative rides a thin line between comedy and horror.

The reader is drawn into the world. A voyeur. Unsure of witnessing an allegory.

The second half will be worth another investment of heavy reading time. We are poised to re-enter the scene at Berghof. How many months have we been stuck together at the mountain lodge? It seems like forever, and in a way it has been. It is slow but clear writing with little white space; thorough but not as complex as Proust. So it is with relief that halftime arrived.

THE BREAK

It hasn’t been long at all. I used the break to enjoy the focused and concise memoir by writers Frederick and Steven Barthelme about their family life and gambling addiction. The read can be done in a single sitting. I am slower and tend to study writing of any style, so it took me three or four days.

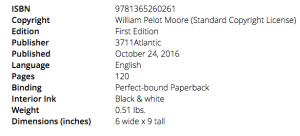

The paperback showed up in the mail in what appeared to be “POD wrap,” a cellophane envelope over what looked and smelled like a freshly minted product.

It is highly readable, uncluttered, and without editing glitch. If I have any beef, it’s that the result of their legal troubles could have been mentioned again. Near book’s end I had forgotten that dismissal of charges was a detail stated earlier in the prolog and wondered about it, upset to be left hanging without a resolution.

The guys deliver their story in an infrequently used POV, a sort of”Third Person Double.” Rick and Steve, as they refer to themselves, unite in a single voice. As we learn how close they are, and how they end up in the same jeopardy, the “we” pronoun becomes more natural and barely noticeable. It’s like a writing sleight of hand. And come to think of it, a play on the book title itself, Double Down.

The content is confessional. Blunt. Very family-centric. The Barthelme parents are depicted in detail: the mother is adorable, liberal, and nurturing; the father is hard-nosed, pragmatic and severe. He is a noted architect with a constantly roving mind, searching for answers far beyond household matters, and the kids suffer for the impersonal nature of it. The story includes a no holds barred look at life growing up with them, life taking care of them in their last days, and ultimately life without them. Their strong presence is reduced to boxes of family memorabilia stashed in an every-day storage unit that seems more a columbarium, a site for reverential browsing. We are left to wonder if indeed the parents are the underlying reason for the boys’ reckless venture into gambling. But can we blame them when the family inheritance is put at risk?

The excursions to the Mississippi coastline and its pre-corporate casinos of the time (80s and 90s) are vivid. On arrival we see the older casino days with slot coins in the till, flashing lights and noise, pit bosses, and cigarette smoke. Characters everywhere. Folks who love blackjack and slots will eat up the actual gambling scenes. And there are things to be learned along the way: the lingo, tips, tricks, protocols…and repeated warnings that the player always loses in the end.

It’s a surprise to read that author Mary Robison (her novel Subtraction is a masterpiece) often tagged along on the casino binge trips. In “Double Down” she is described as tall, good-looking, and in a black jumpsuit appearing very thin, “like scaffolding.” Who can forget such an image?

The arraignment and city jail scenes are terrifying (and highly relatable during this present time in our history when Trump and his crew are being arraigned, though with gloved hands and royal motorcades). As the Barthelme brothers stood in the lower jail waiting to be booked, they silently observed the folly and abuses of an over-stretched system. In this chapter, the memoir read like an engrossing police procedural novel.

The deepest and saddest parts of the narrative are the sons’ depictions of their parents, the father especially. There is love, loss, guilt, blame, fear and loathing. They let us see through the windows.

Is their gambling spree and subsequent arrest something they can pin on genes or the way dad raised them? It’s left as an open question. For me, I draw no judgments. While fiction has the liberty to go anywhere, memoirs have a borderline. The guys pushed close to it. I stepped back, having been behind their family curtain for the full two hundred pages; I choose to stay respectful of what is, after all, a private matter.